Readers may wonder how the heritage of Khandagiri and Udayagiri, a favoured family destination just outside Bhubaneshwar can qualify as ‘hidden’? Sadly, while hundreds of people converge on these stunning sites over a weekend, few recognize their value and importance in being able to trace a most critical chapter of Odisha’s history.

To the wider world beyond Odisha, history has been taught in an extremely straightjacketed manner – with a version that speaks of Ashoka entering Kalinga around 262 BCE, devastating and conquering the land, in the process. Had the Khandagiri and Udayagiri caves not existed, no one would have known of the reverse attack that followed decades later.

Sometime in the second century BCE, a man called Kharavela ascended the throne of Kalinga. He was the third ruler of the Mahameghavahana dynasty of kings. Coming to the throne at a time when the Mauryan empire was at a low ebb, he proved himself a capable military leader. In the twelfth year of his reign, he led an expedition into Magadha where he made the Mauryan King Bahasatimita bow to him. On his return, he brought back the Jain idols that had been taken away to Pataliputra by the Magadhan kings in their attacks on Kalinga. He also enabled Kalingan conquests in areas beyond Magadha.

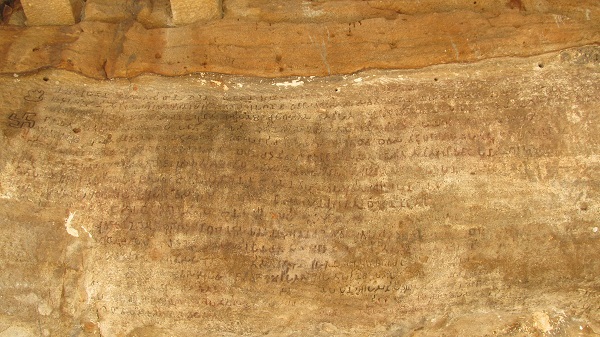

How do we know all this about Kharavela? Because he tells his story himself. Via a detailed message carved on stone, known to historians as the Hathigumpha inscription. The inscription is found on an overhanging rock inside the Udayagiri caves, part of what is popularly known as the Hathigumpha or Elephant Cave. Incised on rock in Brahmi script, the inscription extends to as many as 17 lines, with every line describing one year in the reign of Kharavela. Sadly, with 13 out of the 17 lines having suffered some damage over time, there is much about Kharavela’s story that remains obscure and keeps historians occupied in speculation.

Why did Kharavela choose this particular spot to tell his story? It may not have been a random selection but a power statement on the part of the Kalingan ruler. Standing in front of the Hathigumpha, a visitor can see the Dhauli hill on a clear day. Dhauli is believed to be the site where the brutal Kalinga war was fought and is the site of several Ashokan edicts. In his book ‘The Ocean of Churn’, writer Sanjeev Sanyal opined that Kharavela, by deliberate decision or chance, had found his unique way of saying that he had sacked the Mauryan capital.

Beyond Kharavela, the two cave complexes are marvellous examples of the art and architecture of the time. With over thirty caves between them, they were originally meant for use as prayer cells for Jain monks. Several caves have double storeys, while a few have pillared verandahs. There are more inscriptions beyond the one in Hathigumpha and a wealth or carvings. The Ganesha Gumpha at Udayagiri tells the story of the elopement of Bassavadatta, Princess of Ujjain, with King Udayana of Kaushambhi. Amazingly, this story is not told in words, but via figures carved on stone. Khandagiri, home to a functional Jain temple, is equally superb in terms of the detailing of its stone carving. Its Barabhuji Gumpha, for instance, is named for two carved images of twelve armed devis.

These caves represent a fascinating chronicle of Odisha’s past and in their own way, are no less stunning than, say, the Sanchi stupa. Bringing out a narrative of Odisha’s history that the nation has little understanding of, they deserve their moment in the sun.