Medieval baolis – or stepwells – are so much a part of daily life in Datia that most people don’t think of them as heritage sites. For people like Bhanu, who lives on the outskirts of the town, the day begins each morning with him pumping water from his 17th century well to nurture his kitchen-garden and his cattle. It is unlikely that he has ever consciously thought about who built the medieval structure that gives him his water. Perhaps it is time that he should.

Just as people of Madhya Pradesh gain immensely from the irrigation projects of our current government, subjects of princely states also benefitted from the generous waterworks of rulers, in centuries past. The well or baoli that Bhanu draws water from is a large, multi-level structure. However, it is an exception, with access to its aquifer intact. In most cases, the stepwells of Datia are no longer in use and stand like stragglers of history, shorn of their raison d’etre. Today, we examine a few of these traditional baolis in Datia town and villages around:

Baladar ki baoli: Datia’s most attractive stepwell is an 1810-creation of the princely state’s ruler Parikshit. It is a large double storied structure built in an octagonal shape with a balcony that covers its upper level. At the edge of the balcony, overlooking the well-shaft are stone elephants. It has seen better days, with the plaster falling off now and the elephants crumbling. The front of the well houses a small courtyard where water channels converge on a Shiva shrine under a canopy. Once the focal point of the community around, the place is little-visited now.

Chandewa: East of Datia town on the road to Bhander, a fort-like structure looms on the right. Nothing outside indicates that it contains a stepwell, a large one at that. A long flight of steps goes subterranean towards a deep well-shaft. Pillared corridors line the sides, ideal places to escape the oppressive summer heat. Records indicate the well was repaired by Orchha’s Bundela ruler Bir Singh in 1618, also mentioning that the work was done over a pre-existing well which dated to the 11th-12th century CE. The place comes alive during Maha Shivaratri, when the faithful make a beeline for the Shiva temple that lies beyond the stepwell, amidst fields.

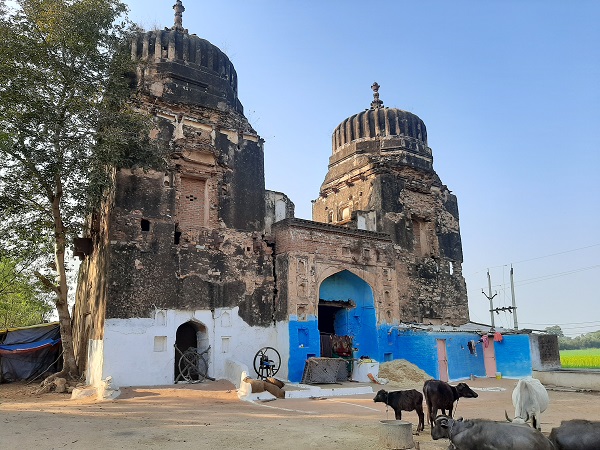

Sirol: Bir Singh constructed another baoli north of Datia town, indicating the town was a magnet for medieval travellers, who rested awhile at the baolis before reaching their destination. The Sirol baoli is entered via an arched gateway flanked by two huge towers, both in the trademark Bundela style so prominent at Datia and Orchha. The place, though a state-protected monument, is now lived in by a peasant family accompanied by their dogs, cats and cattle. Once a visitor gets past this menagerie, he finds himself in a stepwell identical to that of Chandewa, except that it is even larger.

Khadauna: The Bundela stepwell pattern is seen once more at Khadauna, further north of Sirol, close to Indragarh. This baoli is entered via a gateway painted blue and was built under the patronage of a Bundela princess called Kunjawati, daughter of Bir Singh and sister to Hardaul Shah, a cult figure who forms the basis for many folk ballads. The distinct feature of the Khadauna stepwell is that is now a temple. And apart from the main deity, the shrine-stepwell houses one little-known aspect – a tiny carving of Kunjawati, worshipped as a goddess, is housed in the depths of the stepwell. This legend of Bundelkhand lives on, four centuries after Kunjawati’s passing.

Sirsa: This otherwise simple circular well is an enigma. It could have been classified as another Bundela baoli except for extensive usage of temple stones along its walls. The only conclusion that can be drawn is that the material of a 12th century CE temple – dated basis the stone carvings – was used when the stepwell was restored during the Bundela period.