The first time I saw Sreedhar, he made a peculiar gesture – of sniffing at me. When I asked him the reason, he said he was making sure that I was not wearing any ‘scent’, in his parlance. It was ‘khatarnak’ (dangerous) was his view. As a city-dweller, I couldn’t quite fathom why a scent should be dangerous in a forest but the answer soon became apparent.

CHALLENGES: This was my second foray into Pahargarh, Morena, north Madhya Pradesh. The objective was to explore the painted rock shelter near the village. The first foray had been nine years earlier and had ended in a dismal failure. Arriving there late one winter afternoon in 2012, I met a member of the royal family of Pahargarh who pointed out several gaps in my preparation – (a) The rock shelters were not IN Pahargarh but about an hour or so away, hence more daylight hours would be needed to reach them. (b) The area being somewhat unsafe, an armed escort would need to be arranged for which I should inform the local authorities prior to arrival (c) Someone from the royal family’s staff would need to come with me to point out the way and (d) The vehicle I had come in – a hired sedan out of Gwalior – was unsuitable for the trip and a vehicle with higher ground clearance would be needed. Like a chastened invader, I retreated, determined to return later.

The return took another nine years but this time the preparation was complete. Building on the previous trip, I had reached out and requested for the support from the royal household in advance; accomplished the journey from Gwalior to Pahargarh and arrived first thing in the morning and this time, I was in a Mahindra Bolero, which would prove itself equal to any challenge the dirt tracks of Pahargarh could throw up. But before I speak of Pahargarh further, here’s a note on how to get there:

ROUTE: Pahargarh village is about 104 kms from Gwalior, which is the best base to explore the region. Drive north-west out of Gwalior to Morena town (41 kms), take a left towards Kailaras (46 kms from Morena) and then another left from Kailaras to Pahargarh (17 kms away). The road becomes increasingly narrow as you go on but it’s a journey worth taking.

ROYAL HOUSEHOLD OF PAHARGARH: As forts go, that of Pahargarh (picture below) is rather small. The high battlemented walls contain an inner structure where the royals still reside. The fort precincts also house a bank and a post office, which were probably also located here for reasons of safety – remember this is the Chambal, once an area notorious for dacoits.

I was welcomed by Shri Ravi Singh, the eldest member of the Pahargarh royals and his younger brother, Shri Shatrudaman Singh. They belong to a distinguished lineage of Rajputs, and their ancestors fought alongside Rana Sanga in the Battle of Khanwa (1527) against Babur. That defeat saw the clan moving to its current location, from Sikar in what is now Rajasthan. Their story is long and fascinating and shall be narrated elsewhere.

The family’s hospitality and encouragement made my visit to the painted rock shelters of Pahargarh possible. Painted rock shelters are perhaps the hardest form of heritage to locate – they is the proverbial needle in a haystack. To help, they sent along a person from their establishment. This person knew the approximate location but to pin down the exact rock, he added another individual to the gang – Sreedhar, an Adivasi (tribal) who had spent his entire life in the forests of Pahargarh and knew them inside out. He guided us through the last part of our quest.

Also joining the party were two armed policemen, complete with automatic weapons. (Above: Sreedhar; Below: (left to right) – Dayal, Sreedhar, my driver from Gwalior Gaurav, Rajawat and Seemu, who was sent from the royal family’s establishment)

JOURNEY’S END: We drove another 17 kms out of Pahargarh on a proper, surfaced road. A weather-beaten board pointed to the rock shelters to the right and the surfaced road was replaced by a dirt track. This is where the Mahindra Bolero – with its high ground clearance – proved itself valuable. It made it not just over the dirt track but over rocky ground (ref pictures below) as well, for almost 2 kms. The last part now comprised a walk down a tree-covered hillside, passing by what looked like a seasonal waterfall. And then we came upon the riverbed of the Asan River, or Easy River, as I call it.

THE SETTING: We were in the largely dry bed of the Asan River, a tributary of the Chambal. The landscape looked surreal, the rocky isolation of the river valley a stark contrast to the green of the forest that skirts its edges. As far as the eye could see, there was no trace of recent human presence, the operative word being ‘recent’. The humans that came here did so thousands of years ago and they left their mark well-hidden, in the form of drawings on the cliff walls that overlook the valley.

MISSION ACCOMPLISHED: We were finally at Likhichhaj, Pahargarh, Morena! The ‘chhaj’ is a rocky ledge overlooking the valley formed by the Asan River. It is one – perhaps the most significant one – of several rock shelters in this area that are home to paintings drawn by pre-historic man and those who followed his steps. Collectively, these sites can be termed the painted rock shelters of Pahargarh, which happens to be the nearest village of reasonable size.

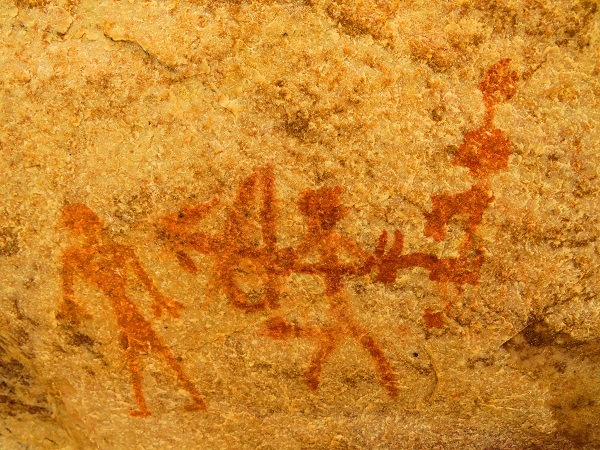

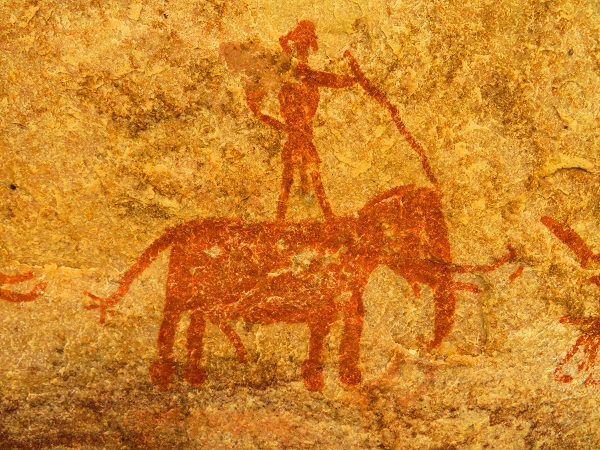

THE ART OF MAN: The Likhichhaj rock shelter is over a hundred feet in width and carries paintings almost throughout that space. Paintings of human figures – some dancing, some hunting, in a group, riding an elephant, carrying weapons including what looks distinctly like a shield. One painting shows a group of people walking, each carrying a stick with their belongings dangling from it, along with some arrows – travellers or men on a hunt?

Another depicts a man standing upright on the back of an elephant.

Yet another looked remarkably like a depiction of a man getting two oxen to drive a cart – is this the oldest depiction of a bullock cart?

The paintings are not all pre-historic; several being made in historic periods too. Alongside the depictions of peacocks, snakes, bulls, deer with huge antlers are geometric patterns, which resemble the yantras used in religious rituals. Most of the paintings are in red ochre, the pigment made by mixing the powdered ochre with water & animal fat, then applied using either twigs.

It is a site every bit as fascinating as Bhimbetka with one significant difference – while the latter achieved UNESCO World Heritage status back in 2003, the painted rock shelters near Pahargarh have never been given official protection and in fact, are characterized by a lack of detailed exploration. The Adivasi community that resides in proximity to this forested region has known about the paintings for years. Decades ago, the area was filled with legends about supernatural activities at the site – a device to keep people away. Most people did stay away – among those who didn’t were the dacoits who traversed the Chambal region. And like their ancestors in centuries past, it is believed that they too found shelter on stormy nights in the same rock shelters, the soot from their fires causing some damage to the paintings. Damage has also been at the hands of more recent visitors seeking to immortalize their names alongside the paintings.

The reason for Sreedhar’s earlier sniffing also became apparent. The site has huge beehives and people who turn up wearing something which gives off a sweet smell get bitten – apparently, the person who visited last was bitten in the eye. That must have been nasty!

A video of the Lakhichhaj painted rock shelter:

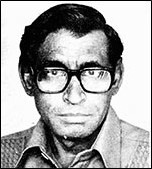

ORIGINAL EXPLORER: While the paintings at Bhimbetka were discovered in 1957, those at Pahargarh became known to the outside world only in the late 1970s. Perhaps the biggest contribution was made by two friends, Prof DPS Dwarikesh (below) and Shri Ram Sharma.

The former had roots in Agra and was a professor of linguistics at the Western Michigan University in USA while the latter was a civil engineer from Pahargarh. Made aware of the presence of these sites, Dwarikesh led a research team to the place during a sabbatical in India, in 1978-79. The journey that I made in the comfort of a vehicle was made by him partly on camel-back and partly on foot. What he saw made him realize the similarity between this site and the findings at Bhimbetka. Going a step further, he even felt that the paintings may not have been mere decorations but could be taken as ideographs and thus, may even be a forerunner of written language in India.

Dwarikesh’s research also provided evidence of two more things – there was enough game, fruits and vegetables in the forested area to sustain a substantial community and the presence of quantities of flintstones, used as tools. He photographed hundreds of paintings, and believed the number could run into thousands. The dating of the paintings remains a matter of debate. While carbon-dating has shown some to be as much as 20,000 years old, others are of much later periods. Even the tools and weapons depicted in some paintings indicates later periods. Lakhichhaj is a veritable portal to man’s progress – and it is only one of several such shelters in this area. Today, Dwarikesh and Sharma have both passed away. Unfortunately, Dwarikesh’s work could never reach a logical conclusion, stymied by India’s red-tape.

But despite the years of neglect and some damage, the sheer isolation of the area and presence of dacoits in the region till some years ago has enabled the rock paintings near the Asan River to survive. As stated by noted archaeologist Erwin Neumayer in his book ‘Prehistoric Rock Art of India’, rock art flourishes with neglect, and decays with attention. This holds true of Pahargarh. In a country where development of cities has swallowed rock art sites of great significance, isolation has saved Pahargarh. During his lengthy study of Indian rock art, Neumayer also visited the Asan River region and the paintings here find mention in his books. However, given that many of the paintings in this area remain unseen, Pahargarh awaits a more detailed study that will reveal their full extent, nature and place in history.